South Africa, Wingshooter Style, The Western Uplander (Winter 2001)

South Africa, Wingshooter Style, The Western Uplander (Winter 2001)

Don Terrell stood in green wheat shoots ten yards from a wall of thatch grass growing along the fence. Behind it guinea fowl were rattling like castanets as a half-dozen field hands drove them, whacking corn stalks and singing out the Zulu equivalent of “shoo birds, git up there” the way we did in South Dakota 40 years ago.

Don waved “get ready” to David Brashear standing a hundred yards down the line. And then thirty salt-and-pepper birds shaped like light bulbs with wings sprang into the blue African sky. Two Beretta autoloaders sounded whump whump whumpity whump and then fell silent while both men fumbled for more red shells as big, easy targets flapped overhead. The chunky birds glided into yellow grass under naked umbrella thorn trees, flickered their wings in the mid-morning sun, and were gone. Rick Lemmer, our professional hunter, and George Haine, landowner and host for the day, stepped out of the corn with Rick’s German shorthair, Cocoa, at heal. “Okay, gentlemen. Let’s go have some fun.”

David and I had joined Don Terrell, a hunting travel agent with Wings, Inc., not just to shoot guineas, francolin, quail and pigeons but to discover South Africa, to participate as part of its eternal ebb and flow of life. We stayed with Rick’s fifth-generation farm family, ate at the family table, and hunted over the family dog. This was the land Shaka Zulu once ruled, murdering enemies and subjects alike. It looked like South Dakota without its silos and grain elevators. Instead of sunburned German farmers, Zulus drove the tractors. Instead of gray partridge and ring-necked pheasants, francolins and helmeted guinea fowl foraged and loafed amid the grass and corn. Little quail squirted from dense thatch. Pigeons fled from tree groves. Once shot at, the guineas ran at the sight of man, ran far and flushed wild into big pastures where they ran some more, their sharp heads gathering intelligence like periscopes above the waves of grass.

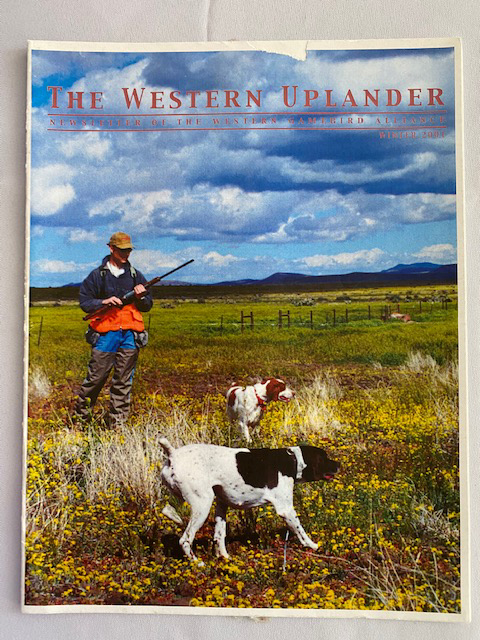

Our first shoot was like a Dakota pheasant drive, which shooed the flock out of the corn and into the grass where they were supposed to hold for a point. Cocoa and George’s orange-and-white pointer held about six of them that we shot like opening-day roosters back home. And then the easy hunting was over.

“There they go!” David Brashear shouts and points toward the far end of a standing cornfield. It has been several hours since our early morning hunt and we haven’t had a close flush since. Birds have been running to the ends of the cornfields and far out into the grass. Now forty of the tailless guineas are flying to a bordering pasture. “We must surround them or they’ll just keep running,” George says. “You two swing way around there and wait behind that little kopje. Then we’ll push them to you.”

David and I jog to the end of the corn, sneak down a grass waterway, pass a drooping apartment complex of weaver finch nests, flush a tiny duiker antelope that dashes away like a baby whitetail. A gang of slouching ibises abandons an acacia tree, complaining like teenagers shooed from a 7-Eleven. Finally we huddle, sweating, at the base of the boulder-strewn knob. We hear Don, George, and Rick talking as they near. They shoot. Something darts through the grass between us. Duiker. But then come red and blue periscopes cleaving the grass. Guineas are pouring over the kopje, skirting around it, racing away. One runs smack into David and the shooting begins. A half dozen birds jump at the first shot, who knows how many more at the second and fourth, and then most go up while we frantically reload. Once tries sneaking by me in a shallow cattle trail. Several turn back at the crest and flush out the sides. If guineas aren’t second cousins to Dakota pheasants, they’ve at least trained under a mercenary or two some U.N. agency sent over.

Compared to guineas, francolin are easy. At least the first day. These chukar-sized upland birds look like a brand of partridge. We commonly found dirty-gray Swainson’s with their naked red face and throat patches. Lighter colored redwings with cinnamon face, breast and wing feathers were rarer. Common quail and harlequin quail were around, but mostly stayed out of our way, thanks to excessive cover. We hunted in June, the southern hemisphere’s equivalent of our December, but it had been an unusually wet and late growing season. As a result, the grass was dense, most of the corn was still standing, and many hen francolin still led half-grown broods. Naturally, we left those alone, but we did find enough mature birds to get a taste for them. Our best hunting was in grass strips between swaths of reaped mealies (harvested corn). While birds in or near standing corn almost always ran or flushed wild, those in the grass strips held like opening day, single quail. When George’s pointer pinned the first in such cover, I doubted it. “False point I think,” I called out after walking past the dog’s nose without flushing so much as a grasshopper.

“She looks awfully steady. Better try again.” I did and this time a big, brown francolin thrashed its way up through the grass at my feet. A few yards farther up the grass strip, Cocoa locked up, and this time George waded in. A pair of birds erupted. Don took one, I the other.

“There’s another point in here,” George called soon after we’d taken our last two francolin. He wasn’t five yards from where those birds had flushed. Don and I slipped into position. Then two birds launched right in front of me and, despite my best intentions to share, I shot them both. “Sorry. Couldn’t resist that double.” Don and David got revenge later by stepping into the middle of quail twice while I was too far out to shoot.

Although we never set up for a traditional dove or pigeon shoot, we took them opportunistically, jumping many from trees and mealie fields, pass shooting others while walking for upland birds. There were surprisingly wild. Rick noted that pigeon shooting would improve later when food sources were more concentrated. We did not take time to explore higher into the foothills of the Drakensburg (Dragon’s Town) Range where additional species of francolin lived. The mountains climbed to 7000 feet just west of our bedrooms, their snowy tops shining in the moonlight.

“I wonder what the bird hunting is like up there,” Don asked on our last evening as he leaned gazing over the patio rail.

“Don’t know,” David replied. “But I bet we could come back next year and find out.”

…………………………………….

Trip contacts:

Our hunt was organized by Wings, Inc.

Phone 803-713-9900. E-mail [email protected] or check www.wingsport.com.

We hunted with Rick Lemmer of Gangeni Safaris, P.O. Box 112, Winterton, Natal, South Africa, Phone 36-468-1603

South Africa, Wingshooter Style

The Western Uplander

(Winter 2001) By Ron Spomer