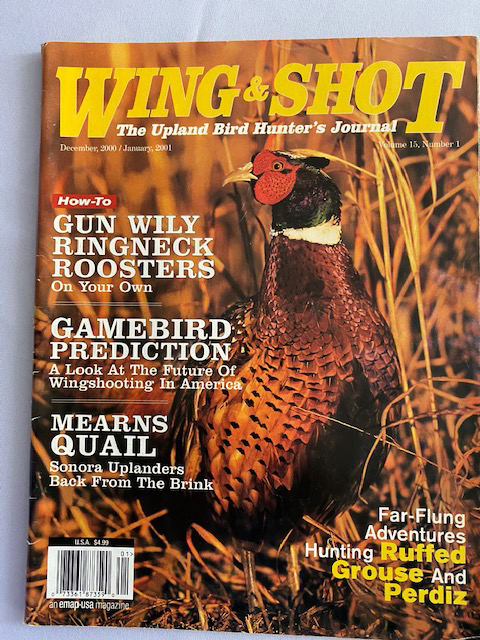

The Argentina Experience, Wing & Shot (Dec 2000 - Jan 2001)

The Argentina Experience, Wing & Shot (Dec 2000 - Jan 2001)

You don’t often hear about Argentina’s flushing birds. They are overshadowed by an all-you-can-shoot smorgasbord of doves, pigeons and geese, plus goodly numbers of particolored ducks. These are what lure hunters to South America, me included. The exciting Perdiz, however, will lure me back again.

“Ahh, ahh, ahh.” Segundo called my attention, pointed to his nose, then to the skinny brown-and-white pointer. The combined sign language of man and beast lost nothing in translation. The young dog was birdy. It went from suspicious casting to intense trailing, cautious tip-toeing. Point. I stepped in front, swished the crew-cut grass and spun at the abrupt sound of short wings behind me. It took me several beats to get the borrowed Remington 1100 settled, find and flick off the safety, lock onto the little brown target and scratch it down.

“Bee-oo-tee-fool.” Segundo exclaimed as Belgium raced out and scooped up my first Perdiz, or more accurately, tinamou.

“Bien tiro. Good shot, no?”

No, not really, but I’d take it, considering the borrowed gun and all. As the bitch pointer returned with the bird, a second that had been hiding at Segundo’s feet lost its nerve and fled. This time the gun fit more naturally and I did make a good shot.

So these were tinamou. Funny looking things, half again bigger than a bobwhite, but colored like a hen pheasant with a decurved, oversized beak to match. Their long, skinny necks put me in mind of sharptailed grouse peeking above prairie grass. Aside from the odd fact they had no tails, they could have passed for some sort of partridge. Taxonomists, however, say tinamou are neither partridge, quail, pheasant, nor any other gallinaceous bird. They are instead cousins to South America’s flightless, ostrich-like rheas, and may represent one of the most ancient of all bird families. Indeed, tinamou have been placed into a scientific order all their own, the Tinamiformes.

To put this in perspective, the order Galliformes encompasses all of the families of chicken-like game birds, including turkeys, grouse, quail, guineafowl, pheasants, and partridge. None of these upland birds are native to Argentina, so the tinamou could represent what scientists call “convergent evolution,” which describes two largely unrelated life forms that have evolved toward similar form and function to exploit similar habitats.

Bats and whippoorwills are one example; one a nocturnal flying mammal, the other a nocturnal flying bird. The tinamou, while having physical characteristics that align it with the flightless rheas, behaves much like our quail or pheasants. It runs more than flies, flushes with a roar on broad, stubby wings and doesn’t fly far before landing. It lives in a relatively small home territory, nests on the ground, lay as many as a dozen eggs, and hatches young that leave the nest and begin feeding themselves shortly after hatching. Like quail, it eats mostly seeds, soft vegetation and insects.

I learned all of that later from an ornithology text. In Argentina I mostly learned that tinamou are one heck of an exciting game bird, which is more than I expected going in. Somehow I’d gotten it into my head that Perdiz were on the order of our sora rails – little marsh birds that flush like overloaded helicopters, their legs dangling as they steadily lose altitude before crash-landing about 20 yards from where they started. That misconception was dispelled by the first bird our party flushed.

“We walk the corn,” Ataliva said, gesturing beyond a barbed-wire fence, signaling his four American guests over. The stalks were cut short, but the rows were choked with corn leaves and a yellow grass. Beyond the autumnal corn, black cattle dotted a green pasture under a sky the color of freshly poured concrete. During our morning duck hunt the sun had risen blood-red before slipping under high clouds that had since lowered and thickened. Except for the 65-degree temperature and a calendar that showed “Julio 10,” it could have been late November back home. Indeed, with seasons reversed, July in Argentina is the middle of winter, the equivalent of our January. The only reason we didn’t have freezing temperatures and snow was because we were near sea level, about 35 degrees south of the equator (comparable to Los Angeles, California).

The dogs loped ahead. Ataliva’s German shorthair was all Teutonic efficiency. Segundo’s pointer was alternately bold and indecisive. A big, orange-and-white English setter was old and conservative, if not, plodding. Instinctively, we spread out like any group of experienced U.S. pheasant hunters. Don Terrell, Nick Tucker and Lee Melchi covered the bulk of the field while I worked the north edge. I was examining my borrowed 20 gauge (having shot all the camp’s 28-gauge shells on doves) when a small gray bird burst out from under a pile of corn leaves and buzzed down the row. I watched it.

“Tiro, tiro.” Shoot, shoot.

“Perdiz?” I asked.

“Perdiz. Si. Tiro.” Segundo again lifted his arms as if shooting.

“What’s the matter, Spomer? Did you come here to fish or cut bait?” Don chided.

“Didn’t know what it was,” I shouted back. Sora hell, that bird had flown like a late-season quail on public land in Missouri. The cornfield blended into a sizeable patch of uncropped grass mixed with annual weeds, where the dogs pointed three more tinamou, which taught me several things.

First, the little birds liked both weedy cornfields and dense weed patches, just like pheasants. Second, based on the way the dogs had trailed, these little birds ran much like pheasants. Third, they flew low and hard. Fourth, I wanted one, which is why I was rather unhappy when our guides waved us over a tight barbed wire fence and into a pasture so overgrazed and cluttered with cow pies, it looked like a pet cemetery. Scattered thistles stood like wilted plastic flowers. Why were we wasting time in this biological desert?

To teach me another tinamou lesson. These surprising birds also lived in short-grass pastures. I could hardly believe it when the dogs began pointing in that short vegetation. Didn’t look tall or thick enough to hide dirt, let alone birds. But within minutes, Don and Lee each knocked birds down and I picked up the pair described earlier. By then our party of six had drifted apart, following different dogs. Since we all were making game, Segundo and I continued, more or less, in the direction Belgium headed, which quickly proved to be toward more tinamou.

Exactly what those birds were doing in that pasture I still don’t know. Apparently they make their living there. Certainly, they proved more than capable of eluding predators in the short cover. Belgium often pointed solidly while we beat and kicked the immediate and near distant ground without moving a bird. Then Segundo would command something in Spanish and the pup (a sickly castaway found on the highway six months earlier) would relocate, twisting and winding, nose near the ground to suck up the scent in the heavy, humid air.

Sometimes these olfactory trails would lead for hundreds of yards, twisting, looping and re-looping before finally ending with another shocking burst of wings. Often we could watch Belgium’s head pivot as she followed a sneaking bird, but we could never see a feather until it was airborne.

“Bueno! Bee-oo-teeful!” Segundo would exclaim when I hit. “Oh. No good, si?” when I missed. His English was limited but considerably better than my Spanish. We talked of guns and game and hunting fields around the world. He guided for red stag, cougars and other big game on big Patagonia ranches and loved rifles. “What caliber you like?” he asked.

“Oh, I shoot many. Two-eighty-four Winchester is one of my favorites.” He looked puzzled. “Like .280 Remington. Do you know that? No? It’s about like the .270 Winchester, only 7mm.”

“Ah! Two-say-fenty! Si. Es good. Bueno caliber. This I use also.” He pulled from his wallet a picture of himself with his rifle and a big Patagonia puma.

As we walked we neared patches of reeds standing in low, wet areas. Here the pup often picked up scent or nailed birds, but usually they led her far across the short pastures before giving her the skip, flushing out of range, or holding so tightly that we practically booted them into the air.

“Ah. There. Look!” Segundo waved me around a small patch of high reeds to show me Belgium on point. I confidently waded in only to be shocked by the rush of a huge bird.

By instinct, my gun was halfway to my shoulder before I thought to ask whether I should shoot. He was a half step ahead of me, already urging “Tiro! Tiro! Si, si, si!”

By tone along I knew this was a special bird. Indeed. Slightly smaller than a sharptail grouse or hen pheasant, here was another species of tinamou, the “big game” of Argentine non-upland upland birds. Long neck, big, decurved beak and beautiful cinnamon-colored primary feathers.

Seeing Segundo’s obvious pleasure in this harvest, I set about looking for another, but finding no more of the smaller species, until nearly dusk. Then, as we crossed a dense grass patch in the cornfield near the car, we flushed four more of the big birds. Shouting and pointing, Segundo urged me to shoot.

I tried the first two, but missed in the dim light. If only we’d turned back 10 minutes earlier.

One of the treats on a guided Argentina hunt is that, at the end of a long, tiring day, you don’t return to a cold camp to rustle up dinner and clean birds. Here you are treated like royalty. While the guides clean your birds and the chef cooks your seven-course meal, you shower and relax with a drink in the drawing-room, warming by the fireplace and sharing adventure stories with your buddies and other sportsmen from around the world.

During our trip, we stayed at three different hunting lodges, Posta del Norte in Cordoba Province, Estancia Santa Maria near Buenos Aires and Estancia San Carlos near Bahia Blanca. Meals are generally gourmet with several courses and an emphasis on surprisingly tender, grass-fed Argentine beef. Dessert is usually the national favorite, dulce de leche, a caramel custard that will have you groaning with delight. Breakfasts are a hearty mix of eggs, bacon, sausages, fresh fruits, breads and pastries, juices and coffee. Lunches are often grilled right in the field and served picnic style when the weather is good, which is most of the time. Unfortunately, after several days of pleasant, sunny dove shooting at Posta del Norte, we lucked into an unusual and unusually durable storm front that brought clouds and thunderstorms for the next week. That’s almost unheard of.

“Well, you bring along a writer and a photographer and you’re really thumbing your nose at the gods,” I joked to Don, who’d arranged our trip through his hunting consulting business, Wings, Inc. Don’s avocation is wing shooting around the world, and he’s always exploring new and unusual venues. “I like to collect new species,” he explained during a lull on the duck marsh one morning. “Here, for instance, we can take close to a dozen species of ducks that we don’t have in America.” Don has hunted several continents, but ranks Argentina first for sheer numbers of birds.

While eared doves, pigeons, and Magellanic geese are treated as agricultural pests in Argentina, Perdiz are revered gamebirds. Limits vary from 10 to 15 per day, depending on the province and species. The big species has a more restricted range and limits are generally much smaller. Actually scientists have identified 40 to 50 species of tinamou. Some live in forests and jungles, some up to 10,000 feet in the Andes. The two we hunted were grassland specialists.

Following a good pointing dog across the flat fields was a refreshing break from the fast-paced but sedentary dove, pigeon, duck and goose shooting. After a morning goose shoot and before the evening pigeon shoot, we’d loose the dogs into nearly any grainfield or pasture and find Perdiz, even in the rain.

“Looks like it’s breaking up. Want to try it?” Don asked, scanning tattered clouds one afternoon. There was lightning to the east and the road was a mudslide. At the gate, Segundo turned out the setter, Gaucho, plus Belgium. The birds, perhaps spooked by the recent storm, would not hold.

“Point. Point.” Don was closest to the setter and jogged over, but two small tinamou squirted out a good 40 yards ahead.

“Point!” I was nearest the dog, but again the bird left early. “They’re running out from under the point and then flushing.”

Two more wild flushes. “Damn. They’re spooky.”

“Look at that cloud. We’re fixing to get wet. Lightning. We’d better get out of here with these guns, “ Don drawled, pushing his steel gun barrel toward the sky, demonstrating the obvious and looking mighty conductive.

Though we hurried, the rain caught us. That didn’t stop Gaucho and Belgium from pointing four more birds. Don scratched one down and I, in a fit of rare luck, neatly stepped on one that spiraled up between us. The 28 gauge (Atiliva had bought more shells) instinctively leaped up and went off as the clouds closed and it began to pour in earnest.

In a country where dove hunters routinely fire two cases of shells in a day, where a 10-box pigeon shoot is normal and a bag of 30 geese average, tinamou hunting tends to take a back seat. That’s fine with me. Leave ‘em alone until I get back down there. They might not be legitimate upland game birds, but tinamou provide all the classic, pointing dog upland hunting you could desire.

Any fast-handling upland gun you shoot well is fine for Perdiz. I’m partial to straight stocked over/unders and wasn’t disappointed with the performance of my 28-gauge Ruger. A 20 would be a more sensible small gauge, suitable for nearly everything, including geese (they fly low and decoy close). Interchangeable chokes are a great idea. So is a second gun, either as a spare or to better match shooting conditions. I used a Gold Mallard Beretta 390 12 for volume shooting at doves in the wind, pigeons, ducks, and geese. While autoloaders are more susceptible to breakdowns, they are also easier on the shoulder when shooting hundreds of rounds each day. My 390 performed flawlessly with nary a misfire or jam.

Comfortable shooting muffs or plugs are a must. Uncle Mike’s leather shooting gloves protected my fingers from hot barrels and sharp action parts during frequent and frantic reloading. A leather-covered shoulder-mounted recoil pad from Cabela’s absorbed excess energy from the buttstock. Finally, pack an easy-access, wide-mouth shooter’s belt pouch. You’ll be fishing cartouches out several times a minute.

ARRANGING A TRIP

Anyone familiar with Argentina could journey there on his own and arrange hunting. But it’s a lot easier to book a package hunt through a consultant like Wings, Inc. (www.wingsport.com; 803-713-9900). All the contacts, arrangements, flight schedules, gun permits, lodging, food, and assorted travel hassles are handled for you, neatly and precisely.

Prices are surprisingly reasonable, starting at around $2700, plus airfare. Non-stop jet service from Miami to Buenos Aires is quick, comfortable and efficient. Or you can fly Lan Chile to Santiago and catch a hopper over the Andes to Cordoba for a stunning view of snowcapped peaks that stretch forever.

The Argentina Experience

Wing & Shot (Dec 2000 - Jan 2001)

By Ron Spomer

Contact: Don Terrell at Wings, Inc. [email protected] 803-424-6107 Cell