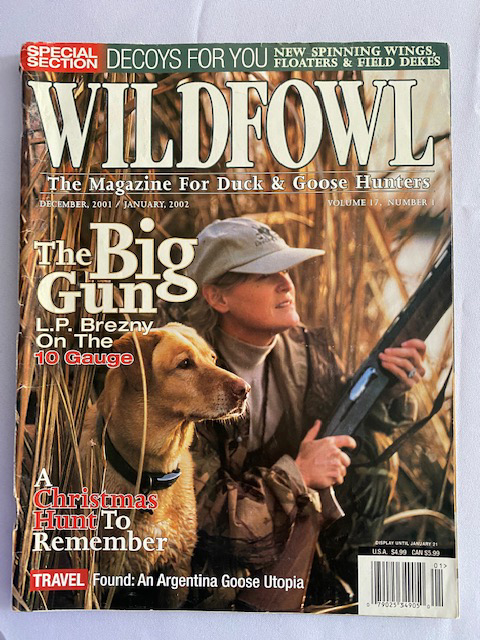

Argentina Upland Goose Utopia, Wildfowl (Dec 2001 - Jan 2002)

Argentina Upland Goose Utopia, Wildfowl (Dec 2001 - Jan 2002)

“Here comes a bunch…” Don Terrell said as he ducked into our simple blind of rebar stakes and camouflage netting. “…from the southwest.” I leaned forward on my five-gallon bucket, peeked over the edge of the ragged material and could just make out plump, dark forms dropping back below the four-strand wire to resume their skimming flight over the muddy, harvested sunflower field, Don whispered to alert Lee and Nick in the next blind over. Their heads were already down.

Onward came the geese, pumping steadily: four white ganders growing brighter, three dark, cinnamon-headed females looking black in the fog. Without circling or calling, they crossed over the wind-sock, half shell and silhouette decoy spread, passing 30 yards in front of us and so low that we had to point our barrels level. Each time the Beretta bucked in my hands the goose trailing behind its muzzle collapsed: one, two, three. “How many did you get?” I immediately asked Don, certain he’s shot at the same birds.

“Just that one,” he said, pointing to a lone goose lying off to the side. “You were laying them down so fast I couldn’t pick one that wasn’t already dead.”

At the risk of sounding like a game hog, I confess I was pleased at this news. This was my first triple on geese, even though I’ve been a hunter for more years than many of my readers have been alive. I grew up in South Dakota and lived for a time near Pierre, goose capital of that web-footed state, but I seldom pursued the big birds. Considering the one-bird limit in place for many years, an effective number of decoys were too expensive to justify. The best-hunting sites were leased to clubs or commercial operators who charged you $15 to sit in a crowded pit blind. Excuse me, but $15 was a bit much for one goose, especially when you weren’t sure if you, the pit captain or the gynecologist two seats down shot it.

Goose hunting in Argentina is very different. There the native upland geese (Chloephaga picta), commonly known as Magellan or Megellanic geese, are so abundant and so reviled as agricultural pests that many farmers pay to get rid of them via poison, aircraft hazing, or egg destruction on the nesting grounds. The only reason any fields are leased is so that outfitters can guarantee daily shooting for foreign clients. The limit has long been as many as you can shoot, but there aren’t enough hunters to really make a dent in the population. Locals rarely hunt geese, so we did our best to make up for this shortfall.

“I’ll go pick those up,” I called out as I leaped from the blind to retrieve my first three birds.

“Wait!” Don hissed. “Here come some more.” I crouched and shuffled back behind the screen of leafy camouflage. “Keep your head down. I’ll tell you when.” Then I heard a few guttural toots and the rush of wings. “Now!” We rose to find geese all around us. Naturally, I picked out the biggest and closest, only to see it fold before I could shoot. Same thing with my next choice. Don was beating me at my own game. Two more likely candidates tumbled to Nick and Lee. Finally, I settled on a lone gander at the edge of range behind our blind and scratched him down.

Geese were not circling us constantly, but it almost seemed that they were. We enjoyed steady shooting from dawn until about 10:30 a.m. Often a second flock would be closing in while we were shooting at birds overhead, and a third bunch would be within sight, just rising over a fence line or roadside powerline three-quarters of a mile away. The more distant birds would not flare at our shots, and if we stayed in the blinds, they’d decoy. “This is unbelievable!” I crowed after shooting my ninth or tenth big goose in less than 30 minutes. “It’s as if they’ve never seen a hunter before.”

“I told you,” Don replied, “It’s the best goose hunting in the world. This is what snow goose shooting would be like if they didn’t fly in such big flocks with all those wary old birds leading the young, dumb ones away.” That may be as accurate an assessment of upland goose gullibility as any. Despite having been persecuted on nesting, and wintering grounds for decades, these birds continue to decoy well because they usually fly in family groups or small flocks, which are always more eager to join feeding birds on the ground than are huge bunches. And when hunters shoot at small bunches, they educate fewer survivors.

There are two races of upland geese in South America, both members of the southern hemisphere’s sheldgeese group. These differ from northern geese because males and females are dimorphic, meaning sexes are marked differently, and they sport iridescent speculums. Most sheldgeese have shorter, stubbier bills than northern geese and are less gregarious, more aggressive and better armed. The belligerent males sport spur-like, carpal-bone knobs on the leading edge of their wings. These are used to battle other males as well as fend off predators, including retrievers and incautious hunters who are often bloodied by the sharp “wing claws.”

The greater upland goose nests on the Falkland Islands where males reach 10 pounds, females eight pounds. Inland, the seven-to-eight pound lesser upland goose nests in grasslands, marshes and Andes Mountain valleys from the tip of Tierra del Fuego north through Patagonia to Bahia Blanca, Argentina, near where we hunted. Lessers are further divided into two color morphs. Ganders in the northern breeding range are mostly white-breasted like the Falkland males. Southern ganders are heavily barred. Females may have cinnamon, sandy-brown or dirty-gray heads and necks blending into heavily barred breasts and orange legs. Ganders’ legs are black like their bills. Both sexes have black primaries and iridescent-green speculums.

The upland goose’s open habitat at least partially explains why they fly so low. There are no trees to force them higher. Mostly they walk about their grassy territories, feeding almost exclusively on grass and other vegetation. But in fall – April through June in the southern hemisphere – southern birds are forced to migrate north where they feed in corn, bean, sunflower and wheat fields. This is the only time of year they congregate in large flocks, but even those aren’t what snow goose or even Canada goose hunters would call big.

A related species, the ashy-headed goose, is slightly smaller than the lesser upland goose. Their heads are gray, their flanks barred black and white and their breasts flash bright rusty brown. Rarely attracted to water, ashy-headed geese nest primarily in the beech forests of the southern Andes. They mix with upland geese on the wintering grounds and are quite common in some areas, though we only shot a few.

The key to getting good upland goose shooting seems to be – no big surprise – scouting. Like northern geese, these birds are fairly consistent in their roosting and foraging, flying similar routes to and from. And, naturally, these change as fields are gleaned. This is where guides really earn their keep. Our outfitter and one or two of his assistants watched flights and glassed area fields while we hunted, ready to move us at a moment’s notice. They also scouted afternoon flights while we gunned wild pigeons in farm-stead woodlots. Next morning, we were again in place for the best goose shooting.

If you’d told me 10 years ago I’d be jetting to Argentina to hunt geese and ducks, I’d have laughed. But today, with movies at $10 a pop, ski lift tickets at $75 a day, and Dakota pheasant shoots are $250 a day, three days of exotic, high-volume Argentine waterfowling at $3,300, airfare included, seems a bargain, especially when you realize everything from gourmet meals to bird cleaning is taken care of. And you can hunt perdiz and pigeons, too. It isn’t unusual to shoot a dozen boxes of 12-gauge shells a day on a combo goose/pigeon hunt. Touring Buenos Aires, meeting friendly people, eating more gourmet food than is good for you and observing a different culture are all bonuses.

I wouldn’t know where to begin to arrange such an adventure, but my hunting partner, Don Terrell, did. As president of Wings, Inc., a hunting-travel agency (803-713-9900 and www.wingsport.com), Don spends his working hours visiting wing-shooting venues worldwide. He selects the best, then organizes package trips for clients who needn’t concern themselves with much more than packing clean underwear. Our trip went without a hitch thanks to Don’s local contacts who met us at the airport, guided us through the intricacies of customs and importing firearms, drove us to the hunting lodge and guided us to our return flights to the U.S. They even arranged a cultural tour of the city for my layover day. The outfitter had all lodging, meals, guides and bird cleaning arranged as well as decoys ready and optimum hunting locations pre-scouted.

PIGEON SHOOT

Like geese, spot-winged and picazurro pigeons are often viewed as crop pests in Argentina. They roost in eucalyptus groves planted around estancia (ranch) yards and corrals. Since we hunted the morning goose flights, evenings were devoted to pigeons coming home to roost, and they came in waves. Our group spread itself along the perimeter of a roost one heavy, overcast afternoon to intercept birds returning from raids on a nearby olive groove. The farmer was most anxious to reduce their depredations. Decoys on fence posts and in the bare mud of a sprouting winter wheat field decoyed early flights, giving us steady shooting. As the dusk neared, more and more birds poured overhead to land deep in the woods. In just two hours I expended 250 rounds on every shot angle imaginable from angle-incoming-plungers to left-right-rising crossers riding a 2mph tailwind. With this volume of shooting, I found a Cabela’s strap-on recoil pad useful protection even with a mild-recoiling autoloader.

PERDIZ

South America has no true gallinaceous upland birds to hunt, but the tinamous, commonly called perdiz, are a more than adequate facsimile. We found plenty of a quail-sized species lurking and running pheasant-like in short grass pastures and picked cornfields where our guide’s pointers, setters, and German shorthairs would trail them, pointing and relocating until locking up solidly. Even then we’d often flush the powerful little fliers behind the dog’s nose. Apparently, the brazen perdiz were sneaking right out from under the dog.

After a morning of relatively sedentary waterfowling from blinds, it was refreshing to roam big fields behind eager dogs. The shooting was equal to the best open-country quail hunting I’ve seen in the States. The major difference was that perdiz were in singles or pairs and didn’t fly to brush or woods to escape. This made the entire hunt the equivalent of working bobwhite singles in open fields. On average, one dog seemed to find a dozen productive points in two hours. A few specimens of the larger tinamou occasionally surprised us.

GUNS & LOADS

Deciding which gun to carry into Argentina hinges on versatility. Dependability and shootability. You want a tool that will work for decoying geese, pass shooting pigeons and jump-shooting perdiz. By all means take a 3-inch 12 gauge for the geese. Because the average goose shot is 30 yards, we did fine with Argentine 2 ¾ inch, 1 ¼-ounce #4 and #2 lead shot loads, but it’s nice to be able to switch to a more powerful fodder if needed. Our local outfitter supplied us with 1 1/8-ounce lead #6s for pigeons and perdiz.

Dependability might suggest an over/under or even a pump, but, according to Don Terrell, most of his clients take autoloaders and don’t regret the choice. You might fire 200 heavy goose loads in a morning, 250 pigeon loads in an afternoon. That’s a lot of recoil, and an autoloader can take out some of the sting. I went with a dependable, soft-shooting Beretta AL390, which worked perfectly. Carrying two guns is good insurance. Take a 12 gauge and a 20 gauge to match the game or two identical 12s to maintain consistency.

Argentina, Upland Goose Utopia

Contact: Don Terrell at Wings, Inc. [email protected] 803-424-6107 Cell

Wildfowl (Dec 2001 - Jan 2002)

By Ron Spomer